One of the most important and powerful impacts of sports is in the universe of social change, particularly as it relates to diversity and civil rights. The fundamental principles that drive progress in these areas are tolerance, acceptance and cooperation. Sports are a very effective platform through which these principles can be demonstrated. There is no question that sports have played, and will continue to play, a vital role in providing examples of these fundamental building blocks of a civil society.

For example, one of the most significant events in the history of the struggle for civil rights was Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color barrier in Major League Baseball. During a time when blacks were considered, to put it mildly, second-class citizens by many and, more bluntly, less than human by others, the sight of Robinson playing alongside white teammates, all on equal footing on the field, was both instructional and inspirational.

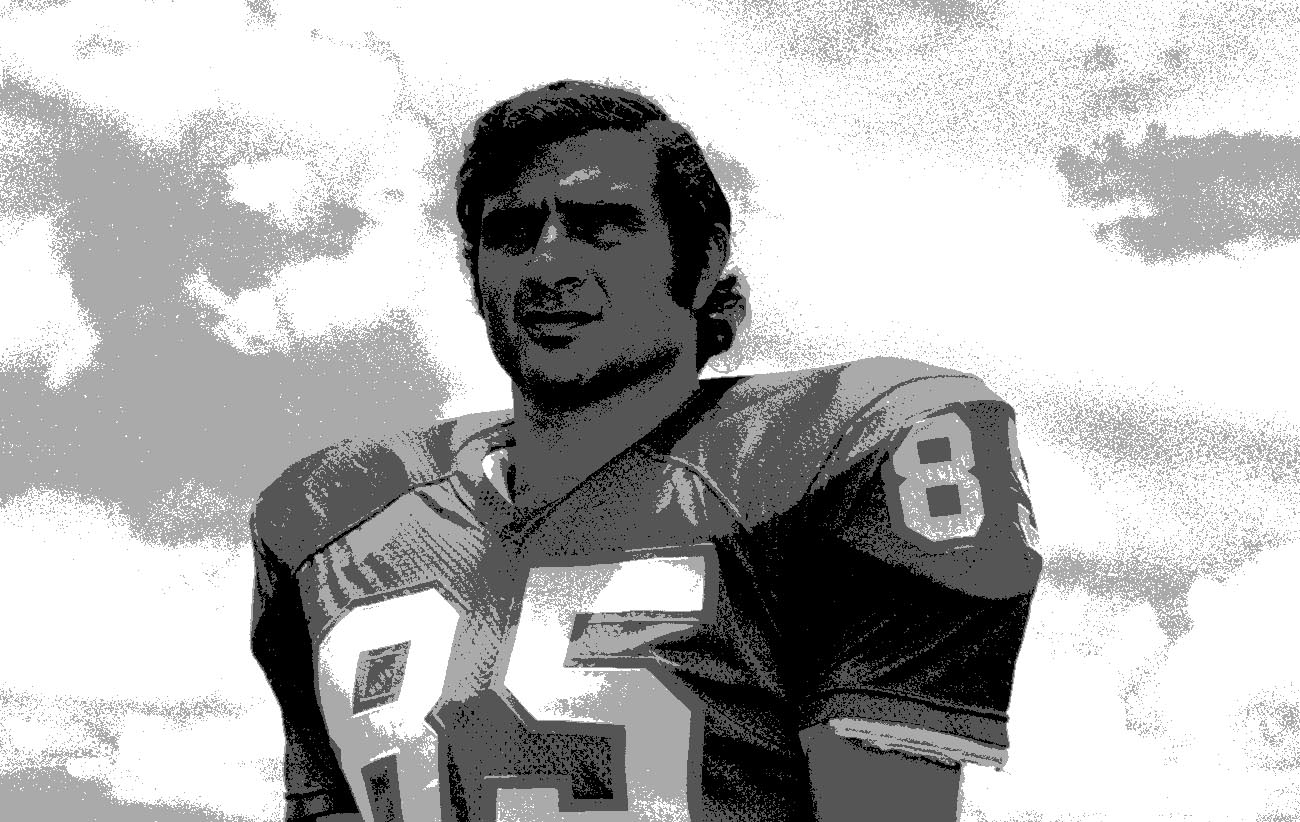

Sports is an enterprise where race, creed and background have, for the most part, little impact on achievement and opportunity, at least on the fields of play. Coaches are interested not in the color of a wide receiver’s skin but in whether that player is able to contribute to the team’s success on the field. Coaches play the best players regardless of color or creed because they want to win above all else. Their jobs and livelihoods depend on it.

Similarly, for the most part, athletes are unusually tolerant and accepting of other athletes. Like their coaches, athletes want to win and a player’s color or background means little if he or she can help in achieving that result.

The sight of athletes working together toward a common goal, sharing in the sweat, pain and sacrifice, provides a powerful example of the possibilities for tolerance, diversity and integration. Sports offer a vivid display of how people, regardless of background, can work together to accomplish impressive things. Seeing black athletes perform on equal footing with their white teammates sparked a light that suggested the possibility that the same could be done in many other occupations and situations. A lot of the progress we have made as a society, whether in business or every day life, has to do with examples of racial tolerance and acceptance demonstrated through sports. When the public sees athletes working together successfully, it provides an example for others to emulate.

There are plenty of stories of whites refusing to stay at a hotel that would not accept their black teammates. Pee Wee Reese went out of his way to put his arm around Robinson in the field, to demonstrate solidarity when Robinson was the target of racial slurs. And, of course, Jesse Owens defeating his white opponents in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a platform Hitler planned on using to demonstrate his despicable notion of white supremacy, resonated throughout the world. In short, sports have played an important role in the world’s ongoing civil rights journey.

This is one of sports’ most powerful and enduring legacies.

But sport is not the only vehicle to play an important role in this regard. While sports may have a more visible public platform, music has the same potential, power and history in promoting tolerance, diversity and integration.

While Jackie Robinson was breaking the color barrier in baseball, there were many bands of all types, styles and sizes demonstrating the power of inclusion and tolerance. Like the stories of white athletes standing up for their black teammates, there are similar stories of musicians doing the same for their black band mates. Like athletes, musicians want to perform their best and don’t particularly care about the color of the saxophonist or drummer as long as he or she can play.

One only has to take a close look at the iconic Art Kane photograph titled Harlem 1958 (or “A Great Day in Harlem”) to imagine what was transpiring on bandstands in concert halls, clubs and bars during the civil rights struggle. Kane used a wide-angle lens to capture a telling photo of fifty-eight jazz musicians sitting, standing and kneeling on the steps of a Harlem brownstone apartment building. Just about all of the jazz “heavyweights” of the era are pictured enjoying what must have been a very lively and entertaining photo session.

Coleman Hawkins is front and center in the picture. A young Dizzy Gillespie is on the right fringe of the group, laughing. And important jazz musicians of the day such as Jimmy Rushing, Count Basie and Thelonious Monk are pictured as well. While the majority of these jazz greats are black, Gerry Milligan, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, George Wettling and Bud Freeman, all white, are also pictured. In addition, Maxine Sullivan, Marian McPartland and Mary Lou Williams represent women jazz musicians. Kane’s photo is a wonderful testament to the fact that music, like sports, was way ahead of the curve in terms of providing examples of blacks, whites and women working together in the equal opportunity arena of a bandstand.

Further, the emergence of “black music” in our cultural landscape served as a powerful example of black culture being accepted and valued, at least by the younger generation. Not surprisingly, it often took the older generation longer to catch on to the inevitable reality that integration was on its way. Chuck Berry’s popularity with white audiences and Elvis Presley, a white kid singing “black” are only two examples.

And the legacy of both sports and music’s role in prodding social change continues to this day in the form of athletes such as Colin Kaepernick and Lebron James and musicians such as John Legend and any number of modern day rap artists.

Clearly, in the area of integration, tolerance and diversity, sports and music have had a powerful impact. Although they are different arenas, their respective potential to provide examples of people of different color, gender and background working together in harmony are, for all practical purposes, identical.

And in today’s increasingly culturally toxic and polarized society, perhaps now more than ever, it is a blessing that their power in this regard is enduring.