For my money, WBGO, which airs out of Newark, NJ, is the world’s finest jazz station. Founded in 1979, WBGO is “a publicly supported cultural institution that preserves and elevates America’s music: jazz and blues.”

Due to the wonders of the internet, you can livestream WBGO anywhere in the world. In this case, I was at the Sun Gate at end of the Inca Trail in Peru. Looking down upon Machu Picchu, at an elevation of over 9,000 feet, a wild thought jumped into my high altitude addled brain. “WBGO? Up here?” So I dialed it up on my iPhone and was soon listening to WBGO deep in the heart of the Andes Mountains. What an amazing world we live in!

As our tour group was getting ready to move on, I heard only a snippet of an in-studio interview with a young jazz musician. I didn’t catch his name, but heard loud and clear him explaining the responsibility of artists to tell the stories of what goes on in society or culture. “As an artist”, he explained, “it’s part of the deal. You have a powerful platform. But you must wield that power thoughtfully and responsibly.”

There has been a lot in the news recently about athletes using their platform to advocate for civil rights and social justice. Similarly, artists and musicians have a rich history of doing the same. Their music or art provides them a platform to shed light on social norms, beliefs and attitudes.

Nina Simone articulated it well, “You can’t help it. An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.”

John Lennon also referenced this responsibility. “My role in society, or any artist’s or poet’s role, is to try to express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher. Not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all.”

Or, in the words of Trent Reznor, founding member of Nine Inch Nails, “I have influence, and it’s my job to call out whatever needs to be called out, because there are people who feel the same way but need someone to articulate it.”

It reminded me of the time, long ago, when I participated in a musical act to protest and to comment on the times and express what we, as peers, felt.

The year was 1971.

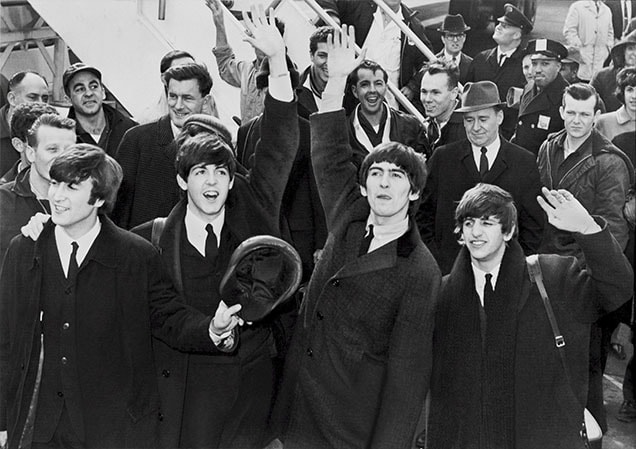

Granted, our little act of activism wasn’t something that led to the kind of cultural change spurred by the arrival of Elvis, the Beatles or Chuck Berry, but within the halls of Little Falls School #1 it reverberated. It’s been argued that it drove Ms. Haynes, the school’s music teacher, to an early grave.

Rather than music class being a joyous and creative experience, Ms. Haynes wielded music like a club, virtually bludgeoning us into submission, all while primly perched behind her piano. She taught the school chorus “her” way, made us sing “her” songs that “her” chorus had sung forever. Songs like “It’s a Grand Old Flag” and “The Wells Fargo Wagon.” Nothing against either of those songs, but did they have to be on the song list every show, every year?

It all came to a head during rehearsal for the spring concert. After the third run-through of “Waltzing Matilda,” we were restless. The times they were a changin’ and we wanted in on it. We wanted to sing at least one song that was timely and relevant. And to us, that meant The Beatles. And Ms. Haynes represented what needed to change.

I raised my hand. “Do you know Hey Jude by the Beatles?"

“Of course, I know the Beatles,” she snapped, eyes piercing over wire spectacles. No matter how hard she may have tried to deny them, those long-haired lads from Liverpool managed to slip through the side door of Ms. Haynes’s musical domain. “I am, however, unfamiliar with the song.”

“It’s a great vocal song with a cool ending. We’d like to sing it” I replied.

“I don’t think the Beatles would be appropriate for the spring concert,” she responded.

But we were dead set on singing it. At the next practice, we asked again. Again, she refused.

So we walked. Five of us, including Skippy Brask, her prize student. We quit the chorus. Our demonstration caused quite a stir in our small suburban elementary school. A group of eighth graders walking out on Ms. Haynes? Quitting over the Beatles? Maybe it wasn’t Woodstock , punk rock or Chuck Berry, but it was our own little rock ‘n’ roll revolution. We drew a line in the sand at “Hey Jude.” We had no clue at the time, but we were using music’s transformational powers to make a statement to spur change.

Yes, I know. It wasn’t Billie Holiday performing “Strange Fruit”. But it did shake up our little grade school in our little corner of our world for a couple of days.

This comparison is by no means meant to trivialize the power of an artist or a song to shake up the world. To the contrary, it is to illustrate the broad, far reaching power to do so.

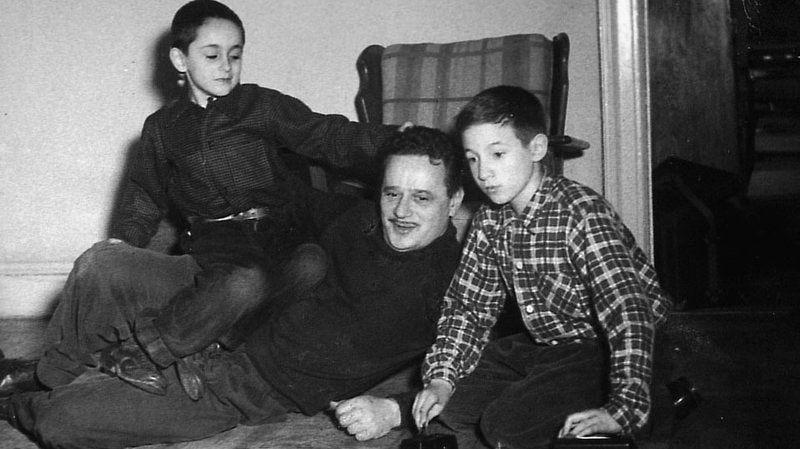

Abel Meeropol watches as his sons, Robert and Michael, play with a train set.

Courtesy of Robert and Michael Meeropol

There is no better song to sharpen that point than “Strange Fruit”. Written as a protest to the inhumanity of racism, it was penned and arranged by Abel Meeropol, a white, Jewish man from the Bronx after seeing a picture of a lynching.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

This is one of the most powerful and haunting songs ever written. In 1999, Time magazine named it the “Song of the Century”. Clearly, it made an enormous difference in raising awareness and shaping the dialogue around the issue of racism in America.

Sadly, athletes and artists continue to face blowback and criticism for using their platforms to raise the collective consciousness of our populace regarding timely and relevant issues of the day. Far too many continue to believe and say that athletes, artists, entertainers and musicians should, “Shut up and play, paint, or sing”, and not comment on the important social, cultural or political issues that impact their lives in profound ways.

But the fact is, perhaps now, more than ever, we need artists, athletes, entertainers and musicians to continue to “reflect the times.” It’s “part of the deal”. And we will all be better off if they continue to meet one of their most fundamental responsibilities to wield that power thoughtfully and responsibly.